Loving and Making God’s Unconditional Love Visible

“Whenever, contrary to the world’s vindictiveness, we love our enemy, we exhibit something of the perfect love of God. Whenever we forgive instead of getting angry at one another, bless instead of cursing one another, tend to one another’s wounds instead of rubbing salt into them, hearten instead of discouraging one another, give hope instead of driving one another to despair, hug instead of harassing one another, welcome instead of cold-shouldering one another, thank instead of criticizing one another, praise instead of maligning one another...in short, whenever we opt for and not against one another, we make God’s unconditional love visible; we are diminishing violence and giving birth to a new community.”—Henri Nouwen in You Are the Beloved (Convergent Books 2017).

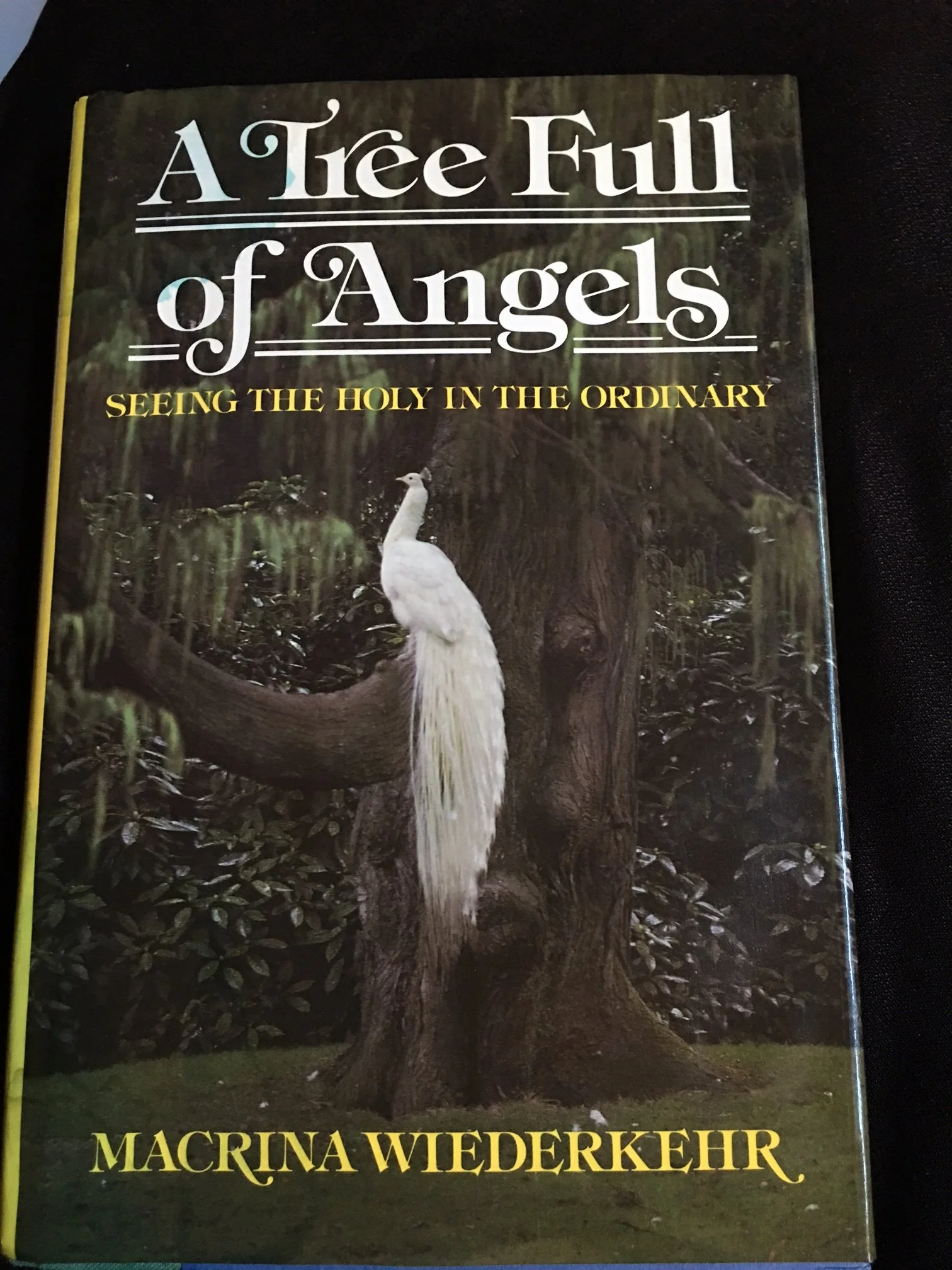

I share pictures of those I know who give unconditional love, members of my family, and, of course, Christ, even on the cross.

My image is that I am a loving person.

Nouwen proves me wrong.

I rarely love my enemies or anyone who harms me, my family, or my friends.

I am just scraping the surface of forgiveness.

I bless less frequently, as my excuse is that deacons are not supposed to bless! Sounds like a Pharisee!

I know subtle ways to rub salt into wounds.

I also have mastered the cold shoulder.

I often forget to thank others for what they do.

I try to encourage others and offer hope, especially to those grieving. However, I could do better by encouraging and offering hope to those I disagree with.

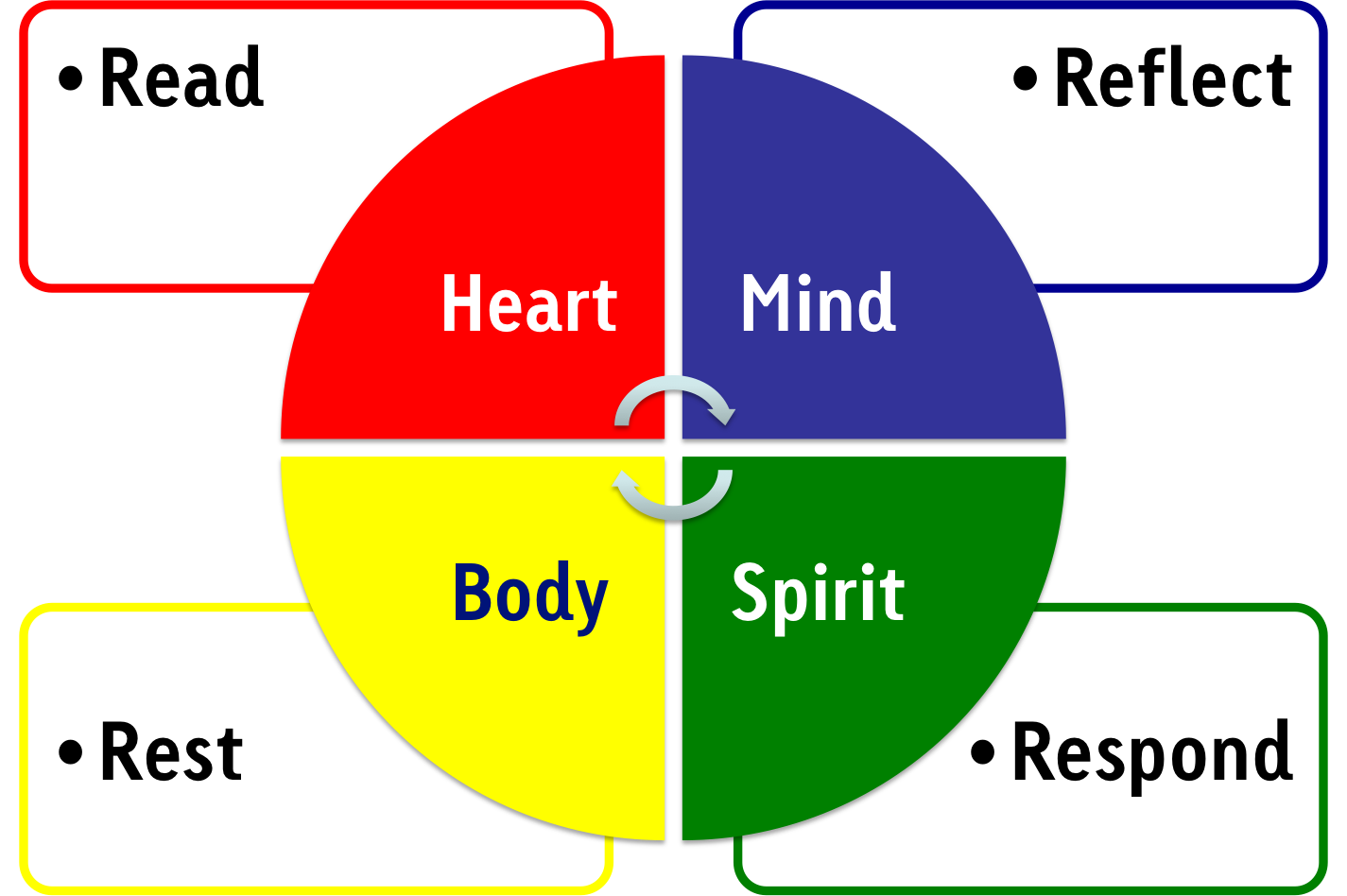

So, Nouwen has given us a Lenten list of loving and unloving practices to pray that the Spirit will change in us.

I also have a part. I am to stop and pause when I have the opportunity to show love or not show love in a multitude of daily situations.

Let us pray that we may love each other.

Joanna. https://www.joannaseibert.com/