Owensby: Changing our perspective

“A gestalt shift is a visual switch of perspective. While looking at an unchanging image, we see first one thing and then another. For instance, in the picture below, you can see an older woman or a young woman.”—Jake Owensby in Looking for God in Messy Places, https://jakeowensby.com, March 3, 2018.

old woman or a young woman?

In his weekly blog, Looking for God in Messy Places, the fourth bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Western Louisiana talks about how we interpret what we see before seeing it. He challenges us to look at some things we think are familiar in another way.

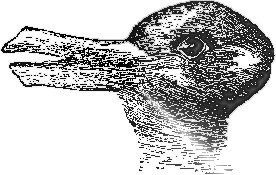

rabbit or a duck

Gestalt shifts involve changing our minds about something.

vase or two people?

I see Gestalt shifts in spiritual direction as well. Spiritual direction is about caring for the soul. Spiritual friends help us put on a new pair of glasses to see God at work in their lives when we did not perceive God before.

Spiritual friends ask questions like, “How is your heart?” instead of “How are you doing?”

Spiritual friends follow a rule of life where we “bend the knee of the heart”1 and “listen with the ear of the heart.”2

Spiritual friends help us find our own sacred space inside of each of us and find sacred spaces outside of us in the world. As a result, we begin to see a different view of the world that Barbara Brown Taylor describes in her book, An Altar in the World.

The Gestalt shift of spiritual friends is that we look beyond the surface and see the Christ in each other, especially in the person we previously had difficulty with.

We begin to see them in a new light, often significantly wounded, just like the rest of us.

1 Prayer of Manasseh, Book of Common Prayer, p. 91.

2 Prologue to The Rule of Benedict.

Joanna joannaseibert.com

Bishop Owensby’s book is Looking for God in Messy Places.

Joanna Seibert. joannaseibert.com