Altering with Intent: The Case for “New” Nursery Rhymes

Guest Writer: Isabel Anders

“When words and pictures work well together, they form something new, something greater than the sum of its parts.” —Lynne Barasch.

“The teaching of children … is where the story of the transfer of knowledge truly begins.” —Simon Winchester, LitHub (4/25/23).

Winchester goes on to explain that the very earliest means of transmitting knowledge “are primarily oral or pictorial in nature: they tend to involve stories, poetry, performance, rock carving, cave painting, songs, dances, games, designs, rituals, ceremonies, architectural practices, and what the aboriginal peoples of Australia know in their various languages as ‘songlines,’ all passed down through the generations by designated elders or specially skilled custodians of each form of cultural expression.”

Some people feel we shouldn’t mess with iconic nursery rhymes. But in fact, many different versions of our children’s classic lullabies and folktales have already been reshaped and shared through the centuries as nighttime comfort and the carriers of new ideas.

However, some story-tale figures familiar to us that meant one thing in earlier times can now signify something totally unrelated in a modern, meme-rich context. In light of this realization, another look at nursery rhymes is reasonable.

Often, a new take on a familiar trope starts with a revised caricature. Political cartoonists frequently draw on the legacy of familiar characters to strengthen their visuals as they make their points. And it usually hits home.

For instance, Humpty-Dumpty sitting on his wall instantly signals vulnerability; George Washington, pictured with a cherry tree, will have something to say about honesty. Biblical themes such as Noah and the Ark (being rescued) or Moses parting the Red Sea (exerting great power) are also shared memes that have retained widespread agreed-on significance.

The reviser of familiar rhymes and their potential messages starts from there. Picturing iconic figures can facilitate a visual “shortcut,” bringing children into a familiar frame or story to convey practical wisdom.

I have turned to writing children’s picture books of “refreshed” nursery rhyme versions to convey values in a culture of sensory overload. I’ve also tried to include some flexibility in the application to show that the child has a choice in how to respond to a situation.

For instance, the older “morals” or intended teachings attached to folk tales tended to be quite rigid and even scary. And too much emphasis on magic and unlikely rescue leads to unrealistic expectations.

Joel H. Morris perhaps sums it up best: “The best re-imagined stories address what is inconsistent about the original text and make it unmissable. To tell such tales again is to tell them for the first time, to weave a thread in the tapestry of what it means to be human.”

By adding, for a new generation, an underlying awareness from Jesus’ Beatitudes of what goodness is all about—how it might manifest in the choices we make, the people we include, the goals we aim for, and the values that endure—the rhymes in my collection are not “New” so much as, I hope, “Timely.”

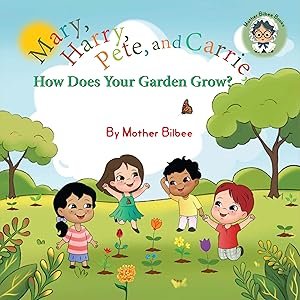

Isabel Anders’ Mother Bilbee Legacy Collection of revised nursery rhymes, picture books for children 3 to 8, includes Sing a Song of Six Birds; Mary, Harry, Pete, and Carrie, How Does Your Garden Grow? and the forthcoming Jack Horner’s Christmas Pie.

Isabel Anders

Joanna Seibert. joannaseibert.com